Global Politics

Globalist Perspective Global Politics Is the EU Destined to Fail?

By Charles Kupchan Friday, June 16, 2006

Globalist Perspective Global Politics Is the EU Destined to Fail?

By Charles Kupchan Friday, June 16, 2006

Well beyond the current problems at Airbus, Europe is in trouble. While many U.S. analysts have long been critical of the European Union, that was not the case with Charles Kupchan, author of "The End of the American Era." He has long been a courageous advocate for Europe. Now that he is changing his mind, it is time for Europeans to take a close look at their own troubles.

During Britain's May 2006 local elections, a Conservative Party long uneasy with integration into Europe routed the Labour Party.

Well beyond the current problems at Airbus, Europe is in trouble. While many U.S. analysts have long been critical of the European Union, that was not the case with Charles Kupchan, author of "The End of the American Era." He has long been a courageous advocate for Europe. Now that he is changing his mind, it is time for Europeans to take a close look at their own troubles.

During Britain's May 2006 local elections, a Conservative Party long uneasy with integration into Europe routed the Labour Party.

Political life across Europe is being re-nationalized, plunging the enterprise of European integration into its most serious crisis since World War II.

Meanwhile, two an ti-EU parties joined Poland’s governing coalition. A European constitution — rejected last year by France and the Netherlands — is now dead in the water. Economic nationalism and protectionism are surging. The Italian, French, Spanish and Polish governments have taken recent steps to protect national industries from takeover.

On a continent that dreamed of eliminating national borders, hostility toward immigrants — especially those from Muslim countries — is causing national boundaries to spring back to life.

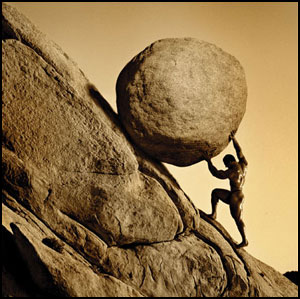

A regressing union.

ti-EU parties joined Poland’s governing coalition. A European constitution — rejected last year by France and the Netherlands — is now dead in the water. Economic nationalism and protectionism are surging. The Italian, French, Spanish and Polish governments have taken recent steps to protect national industries from takeover.

On a continent that dreamed of eliminating national borders, hostility toward immigrants — especially those from Muslim countries — is causing national boundaries to spring back to life.

A regressing union.

ti-EU parties joined Poland’s governing coalition. A European constitution — rejected last year by France and the Netherlands — is now dead in the water. Economic nationalism and protectionism are surging. The Italian, French, Spanish and Polish governments have taken recent steps to protect national industries from takeover.

On a continent that dreamed of eliminating national borders, hostility toward immigrants — especially those from Muslim countries — is causing national boundaries to spring back to life.

A regressing union.

ti-EU parties joined Poland’s governing coalition. A European constitution — rejected last year by France and the Netherlands — is now dead in the water. Economic nationalism and protectionism are surging. The Italian, French, Spanish and Polish governments have taken recent steps to protect national industries from takeover.

On a continent that dreamed of eliminating national borders, hostility toward immigrants — especially those from Muslim countries — is causing national boundaries to spring back to life.

A regressing union. In short, political life across Europe is being re-nationalized, plunging the enterprise of European integration into its most serious crisis since World War II.

Europeans would not be the only losers if the EU continues to stumble. Americans might have to confront the return of national jealousies to Europe — as well as an EU that is too weak to provide the United States the economic and strategic partner it needs.

Unable to adapt

Four main forces are undermining the EU’s foundations. First, Europe’s paternalistic welfare states are struggling to survive the dual forces of European integration and globalization.

European politics is growing increasingly populist — not good news for an EU commonly viewed as an elite affair.

Citizens are fighting back, insisting that the state reassert its sovereignty against unwelcome forces of change.

When they voted down the European constitution in 2005, many French citizens blamed the “ultra-liberal” EU for their economic woes. This spring, rioters took to the streets of Paris to block labor reforms. Italians grumble that the euro has depressed their economy.

In a bind

Especially in France, Germany and Italy, governments are caught in the middle, squeezed from above by the pressures of competitive markets — and from below by an electorate clinging to the comforts of the past and fearful of the uncertainties of the future.

The result is a political stalemate and economic stagnation, which only intensifies the public’s discontent and its skepticism of the benefits of European integration.

Radical inroads

Second, a combination of the union’s enlargement and the influx of Muslim immigrants has diluted traditional European identities and created new social cleavages. Partnership between Germany and Italy will have to replace the Franco-German coalition as Europe’s guiding core.

The EU now has 25 member states at very different levels of development.

Fifteen million Muslims reside within the EU — and Turkey, with 70 million Muslims, is knocking on the membership door. Too many of Europe’s Muslims are achingly distant from the social mainstream, their alienation providing inroads for radicalism.

Unaccustomed to multiethnic society and fearful of an Islamist threat from within, the EU’s majority populations are retreating behind the illusory comfort of national boundaries and ethnic conceptions of nationhood.

Returning to nationalism

Third, European politics is growing increasingly populist — not good news for an EU commonly viewed as an elite affair. Voters see both European and national institutions as ineffective and detached.

In France, the far-right National Front is enjoying unprecedented popularity. In a recent survey, one-third called the party in tune with “the concerns of the French people.”

Polish voters recently elected a nationalist and protectionist president, Lech Kaczynski, who insists that "what interests the Poles is the future of Poland — and not that of the EU."

A generational divide

Finally, Europe is lacking the strong leadership needed to breathe new life into the enterprise of union. Many of Europe’s Muslims are achingly distant from the social mainstream, their alienation providing inroads for radicalism.

Governments in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome are fragile and distracted, preoccupied by the challenges of governing divided and angry electorates.

Generational change is exacerbating matters. For Europeans who lived through World War II and its bitter aftermath, the EU is a sacred antidote to Europe’s bloody past.

But this generation is passing from the scene, ceding influence to younger Europeans who have no past from which they seek escape — and no passion for political union.

Creating consensus on union

At least for now, the European Union is merely adrift — not yet about to unravel. Furthermore, its demise is hardly inevitable. Over the past six decades, Europe has weathered many periods of self-doubt and stasis.

But only bold and urgent steps can put the union back on track. With the French government in turmoil until at least the 2007 elections, a partnership between Germany and Italy will have to replace the Franco-German coalition as Europe’s guiding core.

As a former head of the EU Commission, Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi has the instincts and expertise, but will have to convince German chancellor Angela Merkel to make Europe a top priority.

A decisive moment

European leaders will have to give up the pretense of business as usual — and acknowledge the gravity of the current political crisis.

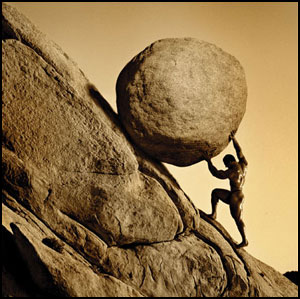

If the EU continues to stumble — Americans might have to confront the return of national jealousies to Europe.

They should scrap the belabored EU constitution in favor of a leaner document that salvages a few key provisions, such as appointment of an EU president and foreign minister and reform of decision making. Only a more centralized and capable union can make the EU more relevant to the lives of its citizens.

Prodi and Merkel will also have to take the lead in forging a compact that embraces both vital economic reforms and measures to integrate immigrants into the mainstream — steps necessary to improve competitiveness, promote growth and replenish shrinking workforces and pensions.

Europeans must face the reality that they have reached a watershed moment. Unless they urgently revive the project of political and economic union, one of the greatest accomplishments of the 20th century will be at risk.

<< Home