Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science Vincent Larivière, Chaoqun Ni, Yves Gingras, Blaise Cronin& Cassidy R. Sugimoto

Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science

Article tools

Subject terms:

Despite many good intentions and initiatives, gender inequality is still rife in science. Although there are more female than male undergraduate and graduate students in many countries1, there are relatively few female full professors, and gender inequalities in hiring2, earnings3, funding4, satisfaction5 and patenting6 persist.

One focus of previous research has been the 'productivity puzzle'. Men publish more papers, on average, than women7, although the gap differs between fields and subfields. Women publish significantly fewer papers in areas in which research is expensive8, such as high-energy physics, possibly as a result of policies and procedures relating to funding allocations4. Women are less likely to participate in collaborations that lead to publication and are much less likely to be listed as either first or last author on a paper7. There is no consensus on the reasons for these gender differences in research output and collaboration — whether it is down to bias, childbearing and rearing9, or other variables.

It has been suggested that what women lack in research output they make up for in citations, particularly in fields with 'greater career risk'8 — that is, fields with long lags between doctoral education and securing a faculty position, such as ecology. But again, there is no consensus on the relative impact of women's work compared to men's.

The present state of quantitative knowledge of gender disparities in science has been shaped primarily by anecdotal reports and studies that are highly localized, monodisciplinary and dated. Furthermore, these studies take little account of the rise in collaborative research and other changes in scholarly practices. Effective policy cannot be built on such foundations.

Nature special:Women in science

Therefore, we present here a global and cross-disciplinary bibliometric analysis of: first, the relationship between gender and research output (for which our proxy was authorship on published papers); second, the extent of collaboration (for which our proxy was co-authorships); and third, scientific impact of all articles published between 2008 and 2012 and indexed in the Thomson Reuters Web of Science databases (for which our proxy was citations). We analysed 5,483,841 research papers and review articles with 27,329,915 authorships. We assigned gender using data from the US Social Security database, among other sources (seeSupplementary Information).

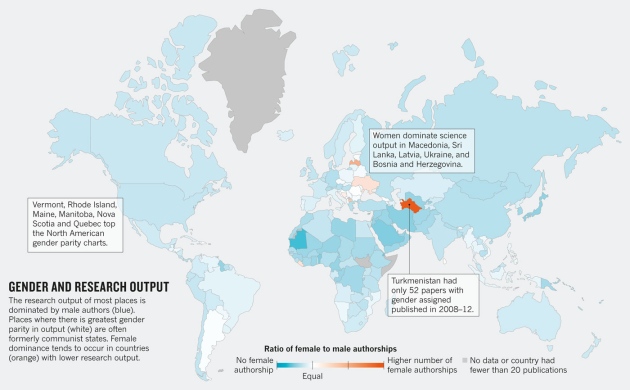

We find that in the most productive countries, all articles with women in dominant author positions receive fewer citations than those with men in the same positions. And this citation disadvantage is accentuated by the fact that women's publication portfolios are more domestic than their male colleagues — they profit less from the extra citations that international collaborations accrue. Given that citations now play a central part in the evaluation of researchers, this situation can only worsen gender disparities (see ‘Gender, output, collaboration and citation’).

In our view, the scale of this study provides much-needed empirical evidence of the inequality that is still all too pervasive in science. It should serve as a call to action for the development of higher education and science policy.

Bias by numbers

Men dominate scientific production in nearly every country; to what extent varies by region (see'Gender and research output'). We probed the proportion of each gender's output by comparing the proportion of identified authorships for each gender on any given paper. For example, for a paper with eight authorships, of which six were assigned a gender, each of the authorships would be granted one-sixth of a paper. These gendered fractions were then aggregated at the levels of countries and disciplines. It should be stressed that these are authorships, not individuals, therefore no author name disambiguation was necessary (see Supplementary Information).

Click here for an interactive version of this map

Globally, women account for fewer than 30% of fractionalized authorships, whereas men represent slightly more than 70%. Women are similarly underrepresented when it comes to first authorships. For every article with a female first author, there are nearly two (1.93) articles first-authored by men.

[...]

Etiquetas: Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science Vincent Larivière, Blaise Cronin& Cassidy R. Sugimoto, Chaoqun Ni, Yves Gingras

<< Home